Not that it is such a surprising ending plot-wise but rather such a perfect combination of comedic and sentimental tone―coupled with a palpable sense of real celebration, breaking the fourth wall―that I was caught off guard, even though I had seen the movie before, by the ending of 2011’s Bridesmaids, starring Saturday Night Live alumni Maya Rudolph and Kristen Wiig. Sitting stiffly on a fake leather couch in a small condominium in Anchorage―to which we had arrived earlier that day, finding a plastic grocery bag of DVDs suspended between the front and storm doors, apparently returned to the condo owner by a friend who had borrowed them―and I suddenly found myself crying as the group Wilson Phillips takes the stage at Lillian’s (played by Rudolph) wedding to sing their famous single, “Hold On.” The singers stand on a small catwalk elevated just enough above the bobbing heads of the wedding guests to make it appear as though they are wading through them; there is a quick pan of the crowd, which, at that moment of watching, surreally emphasized the extreme extension of our TV on its swiveling arm, pulled all the way out to afford the best viewing angle across the combined livingroom/kitchen of the condo’s multi-functional space. Wireless microphones and the band nowhere to be seen: I know there’s pain (I know there’s pain) . . . Why do you lock yourself up in these chains? Several shot-reverse-shots of Lillian and Annie (Wiig) exchanging facial expressions that lend some closure to the prevailing emotional struggles that have dramatized their relationship throughout the movie. Then two wider angle shots from rear and then front of stage, both zooming out and tilting over the crowd, for scene reinforcement and musical movement. Wilson Phillips again: Just open your heart and your mind (Mmm). Then a hard cut to a two-shot of Lillian and Annie again, now side-by-side, Lillian air-drumming the spare tom-tom run (classic ‘80s gated reverb) that intros the chorus, nostrils flared in a comical, muscly emphasis of the otherwise perfunctory rock elements of the pop song, and as the chorus drops Lillian and Annie start synchronously shoulder popping in yet another slightly off-genre response, the whole effect funny and natural and of the feel that it is very much Rudolph and Wiig, not Lillian and Annie, in ironic nostalgic joy, real friends with real history in the somewhat absurd moment of the making of a movie. Someday somebody’s gonna make you want to turn around and say goodbye. Crowd dancing. Fog machine on fountain-pool stage. Wilson Phillips in sequins. Neon laser satin fireworks. And I’m crying; about 10pm in Anchorage and still nearly full daylight.

I thought a lot about Bridesmaids during my weeks alone in Denali, especially that closing sequence. Sometimes “Hold On” would blare so loudly in my mind it was almost unbearable, the clack of river stones or rustling of willow leaves in stark contrast to its studio electricity. The material feel of the movie as a whole was something I clung onto, the clothing and cars and kitchens and homes―I enjoyed remembering them, as I enjoyed remembering the couch in the Anchorage condo and the way the walls coming together around me persuaded comfort and normalcy. Bridesmaids is all about the normal, and, especially, Annie’s inability to find comfort within it. Especially, an inability to find comfort in the normalcy of change: growing (more) up, a friend getting married, class mobility, the real and very lived-with successes or failures that send us each on different trajectories. She is profoundly snared in her own dispossession, can’t get over the ways class and social hierarchies are threatening the dignity of her friendship while simultaneously shaming her for her inadequacies, a dynamic exacerbated by her uncontrolled acting-out. She is lonely, her own worst enemy, and yet she is totally right in a way, something of a radical.

This storyline fits neatly in the dynamics of the outer history in which the movie is situated, perhaps one of the last movies like it that could have been produced. It makes all these heteronormative assumptions; it portrays a society not yet so (transparently) besieged by collective crises (pre-#MeToo, pre-Black Lives Matter, pre-Trump, pre-COVID). It’s pretty white (Lillian’s family is mixed), pretty affluent, yet transgressive insofar as it is a feminist version of a movie like The Hangover, which itself had subverted the rom-com and wedding-comedy genres with an escalating, over-the-top, and exquisitely choreographed humor that somehow also drives the emotional poignancy of the characters’ relationships. In a way Bridesmaids proved that women could be ironic and raunchy, too, and then just on the other side of that statement large swaths of culture would suddenly pivot toward a far more serious orientation that rejected irony and raunchiness wholesale.

Flapping my raincoat dry before bending down into my tent, or feeling swift-moving rivers tugging my feet loose as I stepped deeper into their currents, and all of these fraught, nostalgic thoughts about Bridesmaids would suddenly light up the front of my mind with saturated luminosity. I was hung-up on how recently the remote-feeling era of Bridesmaids had occurred. To be at a wedding! To organize group activities, play out a repertoire of celebratory traditions―I had never particularly cherished these things when I got to do them, but now they represented something lost. I could feel all of the temporal layers of my nostalgia; I was definitely nostalgic for previous forms of nostalgia. There was the idea of a world before COVID, most definitely. But there were also the remembered elements of a younger part of myself, a time when all my friends were getting married and trafficking in these same ceremonial idioms. And then that song: I’m twelve years old again and it’s just ambiently around, on the radio, at the grocery store, on MTV and VH1. My Mom liked it and owned the cassette; we would sing along casually in the car; it was probably the final span of months in my life before music would explode in extraordinary importance, would become the thing on which I staked my very identity, making a song like “Hold On” by Wilson Phillips something I would have to categorically reject.

I identified with Annie. I felt, too, mired in change, by change, with change. All our lives my wife and I have worked hard to be good. We’ve sought careers that helped keep alive what was starved by capitalism, constantly trying to ferret out exploitation, waste, and unkindness wherever they might lurk in our habits or motivations. We did things slowly, deliberately, with hope and calculation. We fostered a fealty to the goodness of the world, of America. And yet we had to admit that we felt evermore betrayed―by change: climate change, economic change, political change, and technological change. We answered this change, in our decision to travel, with more change, a dizzying surplus of it, running as fast as we could as though it might fully detach us, and we could fly above the world and lose nothing in all that change. Where Annie got stuck, we were trying to get unstuck. And we did, we flew, it felt like we were flying, all through that year, through the American West, through the calamity of the pandemic, and literally above the world in order that we be deposited, finally, there, in Alaska. And that was the problem. We felt done.

~

It was a long and late drive back from Denali, and I was grateful that my wife did the entirety of it (a total of 10 hours of driving for her that day), allowing me to sip a little whiskey and brain dump my whole experience, riding high in the cab of the Ram 1500 (a free upgrade, due to lack of inventory) through the distended gloaming of late-summer dusk. She’d prepped a midnight dinner in Anchorage―a pea-protein burger, with cheese and onions―which I devoured. I was embarrassed to be so well taken care of, even by my wife. In part, because I felt at least a portion of failure for bailing. I had imagined an elaborately different version of that day, in which I had hiked all the way to the front entrance to meet her, emerging from the brush by the dog kennels, road-walking, probably in rain, to the “Resting Grizzly” sculpture, where I would drop my pack and run to her. There were so many details to this fantasy: the dogs barking as I bushwhacked closer, declining a ride from a service truck (ignoring COVID, apparently), the clack of my camera on the cement as I dropped my pack, one of the rangers who had helped me earlier still there, and him recognizing me and, yes, applauding. All in the rain.

Didn’t happen, but I was glad to be back, and in a way I was glad to be done with such a major part of our year. Everything after Denali, including the rest of our time in Alaska, had always been an enigma to us. We needed to figure a lot of things out, and so over the remaining few weeks in Anchorage, whenever the rain persuaded us to stay indoors, we pieced it (almost) all together. We set hard dates with our friends in Springfield, MA and those in Harrisonburg, VA, the latter of which put us within spitting distance of the eastern edge of the Great Smoky Mountains just in time for fall colors. Backpacking permit reservations were just opening for the dates we’d be there, so it was pretty much a done deal: we did a little research and were able to pull permits for a loop summiting both Mt. Cammerer and Mt. Sterling. We baked in some time to visit Asheville, which we’d heard so many great things about, and then booked some frontcountry camps farther west in the Smokies. I wrote to a friend I knew who had just moved to Northwest Arkansas, and we looked around the Ozarks just to get the lay of the land. Finally, after poking around AirBnBs in Boise and several mountain towns in Colorado to not much avail, we drifted our search south and found a great rental in Old Town in Albuquerque. We booked it for all of November. That just left December, but then we got cold feet―not ready to write it all the way to the end yet.

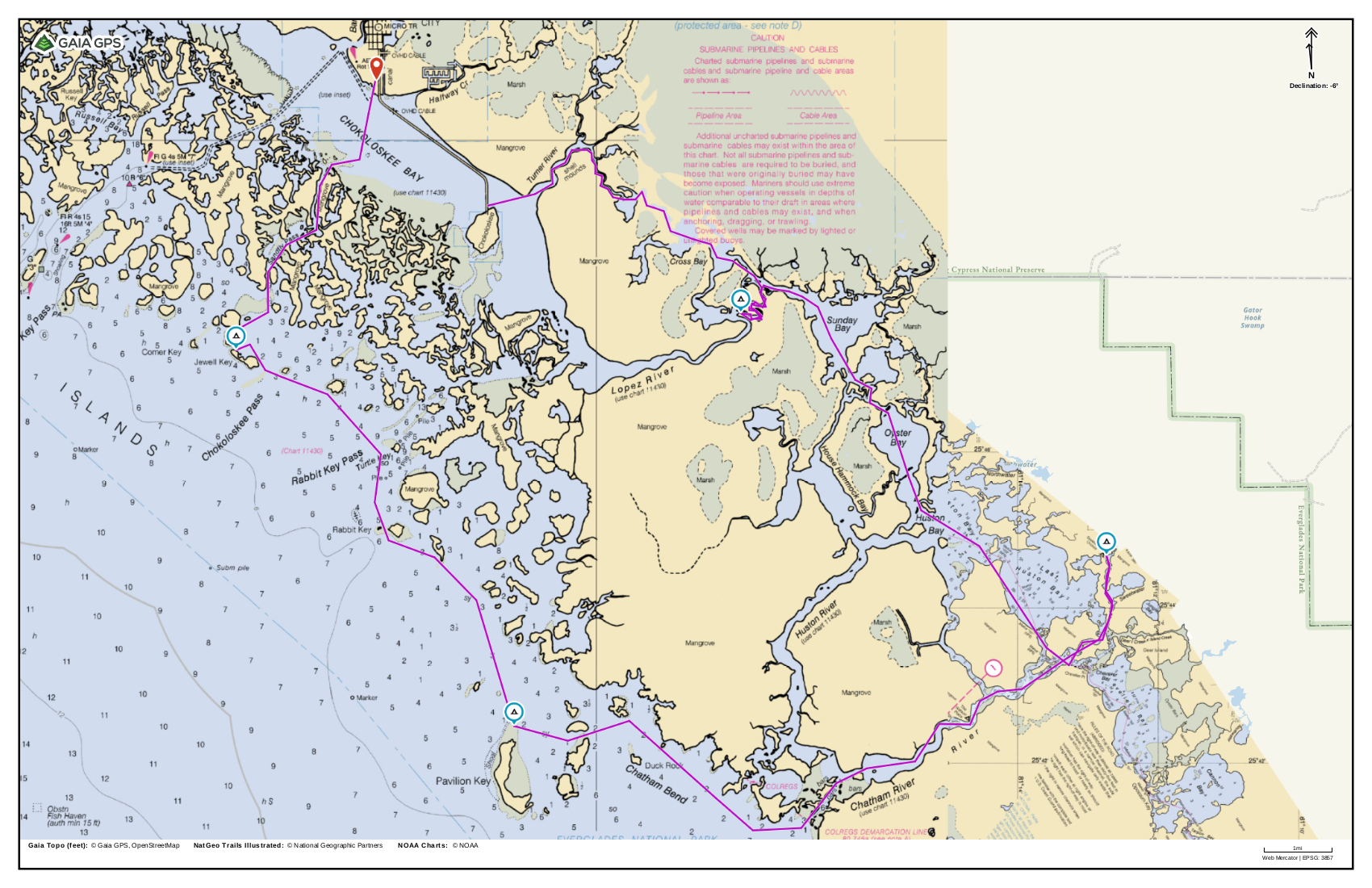

Instead, we figured out the rest of Alaska. As I’ve mentioned, we had been to Alaska a few years before, around the same time and also with a bit of a split between Denali and Anchorage. With the freedom of a few weeks and already satisfied ambitions, it was hard not to just remake some of that previous trip, to enjoy that time as a kind of vacation, an otherwise tricky characterization that we tried to sequester to very limited parts of our year (for instance, just Nashville, just Bozeman, the few days with my wife’s parents and brother in Florida, etc). Part of this decision, too, hinged on the immensity of the state and the relatively few roads that take you across it. We considered booking a bush plane to Katmai, Lake Clark, or even the Kobuk Valley, but we didn’t want the expense nor the COVID risk of another flight. And anyway we were excited for the other places we could go. On our previous trip we had taken an awesome wildlife cruise in Resurrection Bay outside of Seward on the Kenai Peninsula; that seemed a little weird to do again during COVID, but they were operating, and we felt satisfied with their precautions (and our own: stay on deck as much as possible, wear masks). We booked a long tour that promised, if nothing else, glacier views. Then my wife showed me Dale Clemen’s Cabin, which she had researched before, perched high in the Kenai Mountains just to the north of Seward. There was a lone opening, a Wednesday, and we nabbed it―we now had a pretty good couple of days on the peninsula. My wife had also explored a lot in the Chugach outside of Anchorage and had flagged a few hikes she wanted to do with me. Awesome. K., whom I met at Igloo, had kept talking up the historic town of McCarthy in Wrangell–St. Elias National Park. Once in Anchorage, my wife and I were pleased to see that the drive-time wasn’t too bad, and we squirreled it away in our minds. And then I talked to A. on the phone―his dad was coming soon. We wanted to meet him but weren’t sure what we could do that would be safe. Then we found the Harvest Fest, a stripped-down version of the Alaska State Fair, taking place at the fairgrounds in Palmer, just to the north. Perfect.

Atop Near Point in Chugach State Park outside Anchorage

I really enjoyed being in Anchorage. There isn’t a whole lot to the city, but it’s functional and spacious and riddled with paved, forested trails they light in the winter for cross-country skiing, a bona fide conveyance as much as it is a recreational pastime. Our condo was on the east side, fairly close to the mountains, whose relationship with clouds (and, later, snow) was a daily point of interest. The city was moderately closed down from COVID (no indoor dining), but infection rates were very low, and since we’d already been there for a few weeks, in deep wilderness, we were feeling a little more at ease. Not that there was much to do. Mostly I just enjoyed running errands, blasting a playlist that pretty much just alternated the rapper Sampa the Great with the colorfully thrashy rock band Ex Hex out of the open windows of our cowboy pickup truck, an activity that felt cheeky and confusing and delightful. My favorite errand? The farmers market.

For the uninitiated, the autumn harvest in Alaska is a carnival of the monstrously huge. Nearly 24 hours of summer daylight nets insanity: cauliflower heads a foot across, beets the size of softballs, carrots, well, intimidating. And apart from comical size there is just so much biomass―figuring out what to do with a bunch of celery was a bit daunting as I stood there holding its weight in my hand. I was so provoked by all of this. I was probably what you would call “disproportionately” excited about getting to the Harvest Fest, where we would see the prize winners. Fucking pumpkins, I could not wait.

We picked up A. and his dad, a wonderful human being, a Second Indochina (Vietnam) War Vet who’d seemed to do a little bit of everything for work throughout his life, tough as all get out but so gentle, gracious, present. Getting to the fairgrounds, we were dismayed to see so many maskless people, and he barked out-loud about it, but then it just initiated a long and thoughtful conversation about the pandemic as we wandered around trying to find our bearings (which is to say, the pumpkins). We settled into comfort, all of us having been to many state fairs (actually, specifically, the Minnesota State Fair), and then we got to the 4-H barn―that’s where the prize winners were.

They were glorious! You don’t even need me to say this, but the first-place pumpkin looked like Jabba the Hutt. My desire to hug it was very strong. There was a carrot that, I swear to god, at any moment, was going to open its eyes and attack me (I later realized this was my way of remembering the card game Killer Bunnies). There was a turnip with which you could do a kettlebell set, a courgette the size of a terrier. But the best, hands down, was the cabbage patch. What extravagant foliated beauties! The depth of their green was the mystery of nature incarnate, a chlorophyllic concentration that seemed to seep from the age of the dinosaurs through a narrow crack in time. Each was an enormous head with its own countenance. I wanted to get Alice on the phone that she might know how to talk to them. The bright prize ribbons, like a brooche or barrette, only anthropomorphized them more. There was definitely a queen.

My urge to jump up and down and clap my hands―to applaud the cabbages―was embarrassingly kinesthetic; I had to physically tamp myself down, clench my body in twitching excitement. It felt like a culmination of all the Alaskan fruit and vegetable experiences we’d had, though little did I know there would be yet more (keep reading, dear reader). Settling down a bit, I finally agreed to move along, and we enjoyed an afternoon of astonishing normalcy, drinking a few beers at very spaced out picnic tables while listening to a cover band play everything from The Allman Brothers to Rage Against the Machine. Later, we caught a set from fiddle prodigy (and excellent vocalist) Juno Smile, whom I’d known about for a few years and whose dose of country and bluegrass that day welled up numerous resonances from our entire trip, which had always been soundtracked by those genres (flashback to the Endymion Samedi Gras festival in New Orleans and hearing “Tennessee Whiskey” one last time as our unofficial goodbye to the South).

It was a great day. The sun was out but clouds strafed the nearby mountains, dusting them little by little with snow as the hours passed. The fair was at limited, fractional capacity, and you could tell some vendors were grumpy about it, but we were relieved to be able to attend any such gathering at all with the feel of relative safety and responsibility. We walked and talked, indulged a little carnival food, and had commemorative buttons made with a group portrait. Driving back to Anchorage that evening, a setting sun burned a brilliant gold along the Knik Arm, and I was transported back to childhood and numerous summer weekends, my parents driving us home, the sleepy satisfaction of a long day out cradled in that day’s closure.

~

Later that week, we left for Seward. Similar to Telluride, Seward is a small, heavily touristed town hemmed in by mountains, and like Telluride it has ample camping right in town. Most of this camping is essentially a large RV parking lot along the waterfront, meant mostly for fishers (the youth Coho season was just closing, and it was carnage along the outfall stream, pretty amazing―these fish are huge and scarily ogre-like), but there is also a small campground across the main road, set back in some trees, and that’s where we plopped our tent. Only two other parties were there (staying in empty campgrounds was, and would continue to be, a defining activity of our COVID travels). We’d stay there two nights, mostly to accommodate our boat tour, but we did have some free time that first afternoon and drove up to Exit Glacier, where an accessible hike brings visitors within reach of the glacier’s toe. The National Park Service, simply by posting dated signs that mark the glacier’s retreating termination points over the years, has made the entire space into a powerful monument testifying to the effects of climate change. It was a stunning experience to see the immensity of the glacial loss: in the last ten years, several hundred yards; in the last century, over a mile (the first sign posts are on the forested road that approaches the visitor center). And these distances represent extraordinary volume―to mentally fill-in the vacant canyon the glacier has left behind, I had to summon many mountains worth of imagined material. I was reminded of a profound sense of resignation I felt talking to the scientists at Igloo Campground in Denali: see it now, before it’s completely gone. We lingered a fairly long time―it was an opportunity to be still, to really take in the feel of the place, this gateway into the mountains and the massive ice cap―the Harding Icefield―that defined them. It grounded us for what would be, the next day, much swifter (and more turbulent) visits along the wild edges where the Kenai Mountains, replete with tidewater glaciers, meet the sea.

So up and at ‘em the next day, with enough time to get coffee and completely-out-of-the-blue-amazing pastries from Resurrect Art Coffee House―a place we would return to a few times and from which we would purchase some of our only souvenirs from the entire year, these hand-thrown ceramic mugs, one of which I am drinking from right this very moment. After brushing flecks of laminated dough from my beard, we hurried over to the marina to check in. Awaiting us―exactly like our previous tour a few years ago―was a sea otter, a real ham of one, attracting a bit of a crowd on the docks as he lazed buoyantly about, alternating herring snacks with little otter naps, arms akimbo and all.

I mean

On deck, it was chilly in the wet, marine air, and I was grateful for all of our good backpacking clothes, including my rain gloves―ultralight polyurethane Showa gloves I’d brought on every landlocked trip that year, but which in fact were intended for marine work in a place exactly like the boat we were now on. I thought they gave me street cred. And, apparently, I needed it, because as soon as we left the shelter of the interior bay and hit some moderately high seas, I lost any semblance whatsoever of sea-legs and got tremendously sick. For six hours I tried to steady myself with long gazes at the horizon or deep visualizations of the rack of Dramamine I passed several times that morning with boastful indifference while I milled around at the marina. My wife was wholly unfazed. She even drank a fucking beer. Luckily my nausea was tied tautly to the pitching seas, so it was only totally overwhelming while traveling at high knots across the open water, which left me mostly alone on the wind-whipped deck gripping the railing while I fought off both the urge to puke and bone-rattling shivers, spindrift gumming up my eyelashes.

But god damn, it was worth it. The last time we toured Resurrection Bay, it was blue skies and calm seas, but the tour was shorter, mostly visits to nearer coves to see eagles, puffins, and a particularly splendid haul-out of sea lions, set against a backdrop of towering mountains crowned with an extensive cirque glacier. This time the weather and seas were poor with a lot of distance to cover, but so it was that we were captained to some incredible places set in a rugged atmosphere. We took short breaks along seaside cliffs and one particular cove populated with juggernaut sea-stacks, which I could barely appreciate through the prism of my nausea save the clap-and-wash of pitching water slapping at their jagged bases, seabirds swirling among their spruce-bristled heights. We moved swiftly south in between these sojourns, trending toward the western side of Resurrection Bay in order to pivot around the cape of the complex Aialik Peninsula, where we would turn north/northwest to enter Aialik Bay, which we would then traverse quickly to its head, where we finally stopped, in calm waters, at the terminus of the massive, actively calving Aialik Glacier.

It was a profound wall of ice, long enough that it seemed to stretch the limits of my visual horizon. The mood on deck was noticeably giddy, and pretty quickly a crew member fished a watermelon-sized chunk of ice out of the water, and so proceeded a series of guest portraits holding it like a trophy. It was a fun experience and kind of exhilarating to touch a piece of the glacier as though it were a moon rock, but the darker import of it was not lost on me: holding a literal piece of melting glacier, melting right there in the warmth of our embrace (though Aialik’s retreat has been less pronounced than other glaciers). Oh yeah and COVID. But as my nausea cleared, I was able to just be present to the spectacle of the glacier. I took exactly one million photographs. My wife and I teamed up to scan the details of the ice, looking and listening for the initial trickling of ice and water that indicated a section about to calve. My wife caught an excellent video of a particularly large section crashing to the water: at first it’s a soundless sight, the section releasing, hitting the water with a massive, pluming spray, setting off a deep-heaving wave; then the sound: a deep, percussive, suctioning sound that seems to fold itself, over about a second, into a more tightly compacted sound, a bright crackling of ice and water shattering into pieces (we later accidentally deleted the video, OMFG). The captain at one point directed everyone to a large bear on a nearby shoreline, but I’d already had my fill of bears in Alaska and was more interested in this little game I was developing where I would relax my eyes to try and spot all of the seals lounging elegantly on the island-like floes that littered the bay, their bodies surprisingly firm-looking, holding curled tails in the air like some kind of Pilates move.

Aialik Glacier

Approaching Holgate Glacier

We stayed anchored there a little shy of an hour, then moved on, heading back out of Aialik Bay, stopping for a shorter period at the smaller Holgate Glacier, which was still a spectacular sight, squished a little more firmly amid the rock, which gave a better sense of the interaction between the glacier and the mountains, the line where the glacier, in its retreat, was exposing a long-buried surface where pioneer species might soon root. But for the most part we motored on, leaving the bay and entering among the remote and picturesque Chiswell Islands, where we slowed down to spy a sea lion haul-out. And then, as we milled further around, they approached us: a pod of orcas.

My wife and I have only seen orcas in the wild once before, on an early morning ferry in the Puget Sound outside Seattle. The memory is quite vivid: the ferry lurching suddenly to a near halt, passengers looking around a bit confused―then an extremely brief glimpse of their black and white bodies in the water, through the distance and the glare of the gallery windows―a father with his children erupting enthusiastically, yelling “Orca! Orca!” as he ran the length of the rear cabin to catch up with them; and my wife and I, sleepy but glued to the window, watching them via only their dorsal fins, which shrank into imperceptibility as they swam away in the murky gray morning light. This encounter now, in Alaska, was far closer and more prolonged. We counted about five, maybe more. They seemed at-home around the boat, and while the captain, with astonished flourish, told us how lucky we were for this rare treat, I couldn’t help but think that he had a pretty good idea of the pod’s usual location. But no matter: it was amazing. The pod mostly kept to a perimeter around the boat, but one mother and calf swam right up to us, surfacing several times as they approached, at one moment, almost within arm’s reach. I’ve maintained this small inside-joke with my wife in which I mockingly remind her of the time she cried when, on another boat tour outside of Gloucester, MA, we saw a mother and calf humpback whale. I make fun of her, but it’s cry-worthy stuff! The humpbacks, the grizzly sows and cubs I saw in Denali, and now the orcas: seeing motherhood in such dramatic settings, knowing the perils―there are few greater affirmations of the perseverance of life. This single pair of orcas was almost enough to counter the tremendous void of melted glacier I had been imagining earlier. They approached, then swam completely beneath the boat, their black and white patterns kaleidoscopic through the refracting pockets of rollicking water as they disappeared. Then we saw them on the other side, rejoining the pod, the whole of which then slowly swam off, becoming yet again mere dorsal fins―and occasional spumes from their blowholes―shrinking in the distance.

The whole day was, to say the least, full. The rest of it: returning to the marina, dinner, camping, regaining my sense of balance and gastrointestinal stability, is something I only know happened in the abstract. The only detail I can clearly remember is stopping in the small hardware store in Seward to buy a can of kerosene for the heater in Dale Clemen’s Cabin, which we would be hiking to the next day.

Waking that next morning, and the weather had cleared: blue bird day! The glacier-crowned peaks surrounding us glittered in the morning light, and we were excited to be getting into the mountains. Dale Clemen’s Cabin sits along the Lost Lake trail, which runs north and south between a ridge of mountains to the west and highway 9 to the east. Combined with the Primrose Trail, it’s essentially a fifteen mile connector―incidentally, a segment of the Iditarod Trail―between Seward and Kenai Lake. From the southern trailheaad near Seward it’s about 4.5 miles and 1400ft of vertical to get to the cabin. We were at the trailhead in no time, where we paused for a second so I could ask the assistance of a hunter, who was checking his gear, if he had a pair of pliers with which I could twist free one of my trekking pole sections, which had fused stuck with mild corrosion. Almost instantly I shredded the thin aluminum, completely ruining the pole, but I was so distracted by the beautiful weather and friendly conversation with the hunter that I hardly cared. Sharing my wife’s poles, we started up, immediately entering a gorgeous temperate rainforest of old-growth spruce. The forest (and specs of the hike) reminded us so much of hiking in western Washington, it was a little disarming―it was the first time we had been in that sort of environment since we left for our road-trip. We fell into a trained, familiar mode, slogging up switchbacks and taking breaks whenever a particularly impressive tree commanded our attention.

We also, almost instinctively, started hunting for boletes (aka porcini mushrooms) and blueberries. In Washington, we delighted in this sort of foraging. Once, while camping at Royal Lake in the northeast corner of the Olympic mountains, we were privileged with a bolete fruiting event that was bewildering in abundance, enormous caps―the color and size of browning cake-tops―rising, as though proofed, through the duff. Another time, on a late-September backpack to the tarns that surround Yellow Aster Butte in the North Cascades, we ate ourselves sick with blueberries, literally having to lie down among them to ride out the bellyache. Both times were preceded with summer moisture, and this year, in Alaska, it had been historically wet. In Denali, I was continuously in blueberries―any snack I stopped for could be readily supplemented with whatever was around me. Later, on a hike to Near Point in Chugach State Park outside of Anchorage, we encountered a tundra slope filled with boletes, a few caps of which we tenderly stuffed into our lumbar pack and purse, that night frying them for a delicious evening of tacos. With a few days of moisture shifting to ripening warmth and sunshine in Seward, we were tuned, scanning the brush and forest floor with laser-like focus as we climbed.

But, not much. That is, until we attained the main ridge, climbing out of the spruce forest and entering a sub-alpine realm of marsh-soaked meadows and loose hemlock stands, the edges of which sheltered knee-high shrubs beginning to droop beneath the weight of blueberries. It wasn’t a total extravaganza, but there were a few patches that had us lingering for a blissed-out several minutes, summoning the delicate muscle-memory of our previous pillages to twist and pull the little jewels from their twiggy attachments without crushing them, leaving a little crown atop the berry. The juicy pop in your mouth is a culinary marvel. Each individual has a bit of its own character: some tart, some jaw-lockingly sweet, some slightly floral, some slightly citrus, the occasional one with a distinctly onion-like profile, which actually lends a nice, savory weight. Get the right, or any, combination in a handful and it’s a stained-glass sensory portrait of berry, a swirling spectrum of antioxidant sugars and palate gripping tannins that seize your face like water rushing up the nose, as though you had dived into that terroir and found yourself zero-gravity floating in its Mathmagic Land of flavor compounds.

But we had to carry on, eventually resorting to just raking our hands through the brush as we passed. The terrain was opening up into more expansive beauties. At the spur trail for the cabin, we found ourselves in a high meadow with views on the surrounding peaks, rugged with immense glaciation, steeply carved faces shouldering massive snow fields and glaciers, some necklace-like cirques, others pouring down from higher, more distant mountains, lending a three-dimensional depth to the range. The knuckily composition of the slabs and faces of the summit peaks was another echo of western Washington, and the total package, from the glacier carved geology to the moisture-driven vegetation, underscored how much snow these northern Pacific mountains get, the Chugach, in fact, the most in the world―and here, seaside, where the highest summits are barely 6,000 feet. The distant range to the east, across the valley, seemed to track us with a slight, parallax rotation―like the eyes of a haunted painting―as we followed the spur trail to the cabin, a mile and a half section we would end up hiking three times that day, loving every bit of it in the immaculate atmosphere.

We first spotted the cabin as a glare from its roof through the trees, though quickly enough the trail made way down to it. On our approach, we ran into the hunter we’d met at the trailhead, and we continued our friendly conversation in which he assured us that there were plenty of brown (grizzly) bears in these mountains, though the forests allowed considerable elusiveness (I didn’t go into all my bear encounters in Denali). We were puzzled, too, that he beat us to the cabin―he had taken the shorter, steeper winter route, and we squirreled away that option for our hike back. We wished each other well and carried on in our opposite directions. In a few minutes, we reached the cabin. It’s a fantastic little shelter: new, clean, durable, with basic but thoughtful features, especially its large, square table with bench seats and the kerosene heater. But the killer is the back deck, suspended on piles above the slope, among the tree tops that open onto an expansive view of Resurrection Bay and the surrounding mountains. It was a staggering vista to encounter then, even though we had various glimpses on our approach. In part is the absurdity of a building perched there, with such a literally unbelievable view―it welled up a complex of weird feelings I have about property and real estate, the idea of possessing the earth, of possessing a view. I was touched that this was a public place and that it was so affordable to rent (we paid $70; earlier that year, before COVID, we tried to rent a canvas tent in the crowded Curry Village in the Yosemite Valley and were aghast to find that it was $250 a night). We got very excited, very quickly, and debated between just hanging on the deck in the sunshine for the rest of the day or continuing our hike to Lost Lake. It was a hard call: do we take advantage of the incredible cabin, or the opportunity to further explore the incredible terrain? If we stayed, we would probably get antsy. If we went, we’d have to squeeze another 8 miles or so in and would have to hustle. After much deliberation, we opted for the hike.

As we left, we really took note of the trees. The cabin wasn’t surrounded by any old (any old old?) forest. This was old-growth hemlock: twisted, gnarly, statuesque. They had really only started to appear on the spur trail to the cabin, but they would soon define much of our hike to Lost Lake. By now you know I’m a great lover of old trees, and I was surprised by these. No description of the area we read really calls them out, but they are special. Like the whitebark pine in the Winds, the juniper and pinyon in the desert, the live oak in the south, and my beloved Douglas firs and red cedars and hemlocks in the Pacific Northwest, these trees and the forest atmosphere they accumulate expressed such an immemorial reassurance, eons locked in the hard material of their biomass, time and change and seasons and continuous cycles of life and death around them written, with reticence, I’ll fucking say it, with poetry, in their geometries. All I could think was thank god that a government has decided to protect them.

We snaked our way among the hemlocks at a good clip, and after a few miles started climbing out of them, onto a tundra ridge that reminded me of portions of Denali. Eventually we crested a knob and, ba-boom, Lost Lake, glittering in the afternoon sun, attended by a complex of smaller tarns set among peninsulas and terraces. It looked like a fabulous place to camp, though I’m sure weather there can be a treat (I’ll admit I was glad, as the afternoon wind was picking up, not to be fussing with a tent in that exposed place). We really wanted to descend to touch the lake shore, or at least to linger on our perch above it, but we were feeling the pressure to start back―and so again, like many dayhikes we’d done in Washington, the destination was really just a fifteen minute sojourn, a place to eat a snack, take some photos, get a little chilly, then leave.

Peering down at Lost Lake

We hurried again down the tundra ridge and back into the hemlocks, and our efforts rewarded us with a solid amount of late afternoon to still enjoy the cabin. We figured out the heater (it got toasty, fast!), learned the rules of a dice game someone had left behind, started blasting the anniversary playlist we assembled during our Yucca Valley quarantine, and cracked into our bladder of whisky. A deep, long sunset swept across the bay and threw alpenglow on the surrounding peaks. We stoved up some supermac haute cuisine atop a stone inset on the workbench and ate with fervor. We awed on the deck. We destroyed each other in the dice game. We giggled and danced when the music got ripe. It was a bona fide party, the most jazzed we’d been probably since Mardi Gras (or maybe Michigan, though that was a more athletic kind of debauchery). We were snoring before nightfall.

The return view of an absolutely spectacular hike

Hurting a touch the next morning, but we remembered another thing the hunter told us: that he’d seen a couple foraging berries near the cabin. We hadn’t really had time to give a good go of it earlier, but now we endeavored too. We decamped from the cabin pretty quickly and started hunting the nearby slopes, set in the hemlocks and dappled with morning light. Pretty quickly we saw what we were in for―this, this was the extravaganza. Nearly everywhere we turned, every little corner of the forest, were shrubs laden with the plumpest berries we’d yet seen. Many were commercial size. We drifted apart, working different lines filling whatever possible container we had on hand, shouting occasionally to keep tabs on each other (and notify any possible bears). We gorged and drank plenty of water, smoothing our hangovers out. We worked for about an hour, then called it quits, our hands stained a violent purple, which we considered a mark of some esteem, like a good tan line, sea salted hair, a wind burned face. We filled our one liter pot nearly to the brim, rubberbanded the lid on, and set it delicately at the top of my pack, hiking the winter route down where we would eventually run into a couple searching for blueberries themselves (they had a nifty raking tool)―we showed them our hands and pointed up the trail.

I can’t imagine how you could spend a better four days in Seward (maybe ditch the seasickness). Back in Anchorage, and we started putting the blueberries to use with some of the gooiest pancakes to ever smear a plate, and then a blueberry crumb, a recipe my wife has dialed in tight, the sort of thing anyone around it will fall hopelessly into with embarrassing savagery. A few weeks earlier my wife had also taken up the noble cause of banana splits, a series of projects from which we had a good amount of remnant heavy cream―we whipped the last of it, and when it met those berries, in whatever costume, just, cancel everything else. All of this and yet still we had more berries to just eat by the handful, which we did as we lazed around the condo coming to terms with our final week in Alaska. Coffee, handful of berries, and loading a map of the state for one more trip.

I texted A., and he was in: a two-night visit to Wrangell-St. Elias. Wrangell is mostly a fly-in park―if you really want to get in there, you have to take a bush plane (or hike or raft in, I suppose). But two roads skirt its perimeter. The far more popular one is the McCarthy Road (that K. told me about), which edges the park’s southern boundary on its way to the historic Kennecott Mine and Kennicott Glacier. Photos are incredible―you are right at the toe of the glacier, and there are a few facilities and outfitters―but it’s a long, rugged road through a lot of private land, and we were worried about time, our rental car agreement on the bad road (many agreements prohibit driving dirt roads; in Alaska, some specifically prohibit the McCarthy Road), as well as camping options along the way. We opted instead for the Nabesna Road, on the park’s northern perimeter, which is a little shorter and a little less rugged (technically paved for most of it), predominately through parkland with numerous possible road camps and an established campground at a good, central location, the Kendesnii camp. We―almost blindfolded―grabbed some dehydrated dinners from a now quite abused freezer bag; wrapped a whole kit of blueberry crumb, cutting board, and knife in some foil; and loaded the truck.

The trip from Anchorage to Wrangell is worth it for the drive alone. All year we had been keeping a mental list of the grandest stretches of highway we’d driven: that between Escalante and Boulder in Utah; between Aspen and Leadville in Colorado; later, in the fall, the Blue Ridge Parkway between Roanoke and Blowing Rock, NC; then 395 along the eastern Sierra from Big Pine to Mono City. But absolutely wrestling for top position is Anchorage to Glennallen. The first portion is along the Knik Arm to Palmer, which we’d come to love having driven both up to Denali and to the Harvest Festival, as I mentioned earlier. From Palmer, Hwy 1 turns east following the Matanuska River in a long valley (the Matanuska Valley, part of a larger region known as the Matanuska-Susitna, or Mat-Su, Valley) to the south of which lies a massive, ice-locked sub-range of the Chugach, visible on a map as a northern arc of craggy whiteness, like sculpted whipped cream, atop the Prince William Sound. Draining north out of these mountains are a sequence of huge glaciers (the Matanuska, Nelchina, and Tazlina being the notable ones), glittering blue and white and then polished charcoal gray in their debris-laden moraines, which flowed among—then, in mid-September―deeply golden birch and aspen stands that reminded me of a deliciously mineral, tawny white wine. My neck started to strain from being so continuously locked to the right, and we took every pull-out we could to survey the valley below us (and attack the blueberry crumb).

Fall colors along the Matanuska Glacier

Eventually Hwy 1 straightens head-on toward the Wrangells in a perfectly centered approach of the stratovolcanic Mt. Drum. It is an extraordinarily picturesque stretch of road (on a clear day, at least). The symmetrically conical Mt. Drum floats intimidatingly atop the horizon, the quintessence of mountain, attended by sibling peaks (some taller, in fact, though more distant), but Mt. Drum the one who is undoubtedly enthroned, the highway descending in worshipful proskynesis to kiss its feet. Numerous cars were pulled over, photographers dashing to the center of the highway between traffic. I wished we had done the same, but I did manage a serviceable photo through the windshield, whose bug splatters, as I look at the picture now, give it a little vérité. We kept on, passing through Glenallen where we took the northern split, skirting Mt. Drum and Mt. Sanford, stopping for a quick lunch (all I remember is blueberry crumb), then continuing to Slana, where we turned off onto the Nabesna Road.

It was remote and empty, perfectly Alaskan, hemmed in by brush but frequently opening onto expansive views of an immense valley to the south that leads into the headwaters of the Copper River (one of Alaska’s most important watersheds) and the heart of the Wrangells, Tanada Peak being the most visible of its constituents. We passed hardly four or five other campers parked in the pull-outs, folks sitting in folding chairs with views onto the valley, but it was clear that it was busier than it appeared, game unit signs flickering by reminding us that it was moose season. No pull-out camps really suited us, and we eventually made it to Kendesnii Campground, which was surprisingly nice, fairly new, very well maintained (the toilet paper in the outhouse had been decoratively folded, like you might find in a luxury suite (or love motel))―and, it’s totally free, of course. We picked a lovely little site with a trail down to a nearby lake and good views of Tanada, and settled in. There were three or four other parties there, spread out widely, camper vans and RVs towing ATVs and other contraptions, and one hunting party, who came by with a friendly offering of canned salmon and good conversation about the hunt and how the summer season had been (cool and wet). We were also visited by a very large, mangy, and sweet dog―whom we immediately named “bear”―that we quickly discerned was no charge of anyone there but must have wandered over from a private home nearby. Dinner, a few drinks, and an early bed.

Our plan for our one full day was a hike north up the Trail Creek Trail (Creek Trail Creek?) into the foothills of the Mentasta Mountains. There is a straightforward loop you can do, climbing east to a low pass where there is likely good camping, then dropping down and returning south via the Lost Creek Trail. But we were all feeling leisurely and really just wanted to poke up into the mountains to see what we could see, so we didn’t endeavor for the loop. “Trail” here is a bit generous, or in any case these were Alaskan-grade trails: mostly ATV tracks running along the braided creekbed accompanied by boot or game trails if you decided to ascend the banks into the spruce and shrub brush. There was a lot of shallow creek crossing, which we would have ordinarily been fine with, but nights were getting very cold, and we were all daunted by the idea of ice-frozen shoes in the morning. In Denali I had had a similar, sudden repugnance for wet shoes, and I was feeling renewed shame about it―not enough, though, to have me tromping into the creek for faster travel. So the picking got tedious―on several occasions we split up just to find routes around marshes or streamlets, bushwhacking in the willow and alder far more than we anticipated, yelling out to each other to ping our locations and confirm any good ways through. It all felt a bit namby pamby, but I confess that I was actually savoring some of the route-finding and bushwhacking, holding onto the efforts as probably the last of them we would do this year.

It also started to get quite beautiful, the foothills narrowing into a gentle canyon around Trail Creek, the slightly elevated benches there providing more dramatic perspective on Tanada Peak, which at moments was solely lit by a golden shaft of yellow light through a narrow break in the thickening cloud-deck. A few weeks earlier I had been asked to film a reading of a poem I had had in that year’s Best American Poetry, and this was the perfect venue. My wife filmed it on an ipad, myself with earbuds as lavalier into my phone. We did a couple takes but tried to be quick. It is a nervous, rushed reading, midges landing in my mouth throughout it, but I couldn’t have asked for a better place to do a poem, and when I watch it now I see myself as someone I’ve always wanted to be―completely entangled in poetry and wilderness, wind-burned, slate-eyed, in heavy brush in the folds of mountains.

That was about our turn-around point―two opposing shoulders up ahead created a natural gateway into the headwaters of Trail Creek, and while we were tempted to spy into what looked to be a cool new area, it would have meant getting our shoes wet. We headed back, having retained almost nothing from our route-finding on the way in, which made for a long return of yet more bushwhacking. But it was fun. The three of us kept on talking about everything imaginable, especially our view onto the fall and, already, our hopes for the next year, when we might have a new president, when COVID might be beat, and when our lives might land into something with shape, purpose, community. It felt like I was physically walking―clamoring―out of Alaska and into those questions. Interruptions of creeks and marshes, heavy brush, and then we kept on, motivated by the slowly dimming light of the sky and the thinning temperature.

At the trailhead (“trailhead”), we scratched around for some wood and found abundant tangles of thin-branched willow, nice and dry, that we loaded full into the bed of our truck. It was a heaping pile. We drove gingerly back to camp, hardly a few miles, the long-necked dusk starting to twist around the truck, the gray dimming through the windshield splattered with bugs and the sound of a low wind and the gravel beneath the tires. At camp we poured drinks, got our stoves roiling, put on puffy coats, and touched hardly a flick of the lighter to the willow, which we loaded into the fire pit pretty much continuously as the night took hold. And we talked, and talked, and talked―one more good, full-bodied conversation set around a campfire, an experience we were growing rich in that strange year when the world was otherwise impoverished in such real-life socializing. In a few days I would take a picture of my wife in the car rental parking lot, her backpack tall and full and ridiculous looking. We would wait in a baggage line behind moose hunters from Texas who were wheeling a luggage cart atop which was perched an enormous moose head, fully taped up with cardboard but unmistakable for its paddles, which were nearly as wide as I could stretch out my arms. Then we would be back in Chicago. We would eat pizza on a patio in Elgin in brilliant late-September light, my newly licensed niece driving us there. We would tour the expansion of our friend’s brewery, an unimaginably massive warehouse presided over by looming stainless steel tanks several stories in height, through the open receiving doors fluorescent street lights pallid across an empty parking lot in the deep night of Naperville. A few days after that, we would yet again be on I-90, narrowing through the post-industrial lakeshore corridor where a busy East Coast traffic would tighten around us as we passed through Erie, then Buffalo, and onto Massachusetts. It would be strangely warmer, humid, clinging. But for now we were still there in Alaska. It was cold, biting at us, though the fire crackled hot and rapid and big―bright yellow flames like paper. We talked on, and I felt like I came to know something I hadn’t known before, even as I knew that I knew even less.

For a full set of photos, visit here: https://www.amazon.com/photos/shared/r915vIWsTMqMSf-jSZRGeA.WujtBOSl4EHQF5pzlQUq2g